Unpacking Lebanon’s political complexities

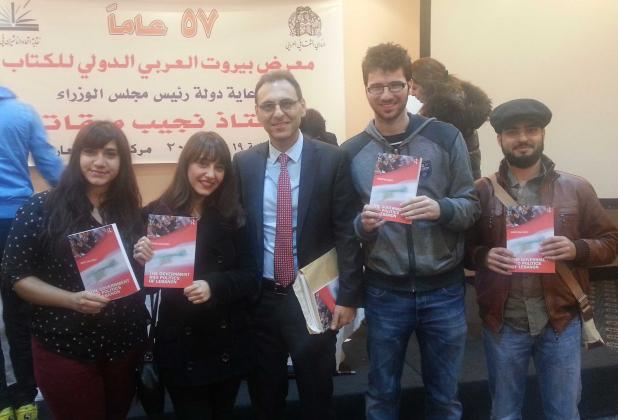

With 18 religious groups recognized in parliament, a complicated confessional system and a myriad of political upheavals, Lebanon is sometimes a tricky place for even Middle Eastern political analysts to understand. In his new book, The Government and Politics of Lebanon, published by Routledge, Dr. Imad Salamey, associate professor of political science, hopes to dispel some of the clouds that surround Lebanon’s political system. LAU put a few questions to Salamey following his recent book signing ceremony at the International Arab Book Fair to learn more.

Can you tell us more about what your book is about?

Dr. Salamey: The aim is to contribute to the reader’s greater understanding of Lebanese government and politics through an examination of the origin, development and institutionalization of the country’s sectarian consociationalism. I examine Lebanese sectarian politics of conflict and concession during different historic junctures, revealing the role of domestic and international forces in shaping the country’s destiny. The book provides a comprehensive introduction to students and readers interested in Lebanon and Middle Eastern studies.

What is consociationalism?

Dr. Salamey: State consociationalism, a term originally coined by political scientist Arend Lijphart, is the manifestation of sectarian politics where power is divided and shared. In my book I assert that consociationalism has been both a blessing and a curse in Lebanon.

Can you elaborate?

Dr. Salamey: A recurrent proposition advanced in this book is that Lebanese sectarian consociationalism has been both a cure and a curse in the formulation of political settlements and institution building. On the one hand, and in contrast to many surrounding Arab regimes, consociational arrangements have provided the country with a relatively democratic political life. A government with a strong confessional division of power and a built-in check and balance mechanism has prevented the emergence of dictatorship or monarchy. On the other hand, a chronic weak state has complicated efforts for nation building in favor of sectarian fragmentation, external interventions and strong polarization that periodically brought the country to the verge of total collapse and civil war.

What does the current political impasse in Lebanon mean in terms of consociationalism or say about its success here?

Dr. Salamey: The book describes post-Doha accords Lebanon as a Third Republic distinguished by four tenants: a deeply entrenched sectarian parliament, consociationally elected president, a cabinet divided between the three major confessional groups and a quasi-Shiite federal arrangement. The current political impasse confronting Lebanon is evidence of a growing rift and disagreement between the different sectarian groups about every aspect of the Third Republic, calling for the foundation of a new political contract. One of the successes of the current regime, however, is its ability to adapt to a turbulent regional environment without totally slipping toward a complete breakdown.

How does this book differ from other books written about Lebanon?

Dr. Salamey: The number of available books, particularly by local authors, is actually quite limited. In addition, the politicization of the subject has left a wide gap between objectivity and personal opinion. This book intends to contribute to fulfilling the gap separating research from the interpretation of Lebanese consociationalism through a comprehensive and academically-robust approach. It responds empirically to the reader’s intellectual curiosity while inviting debate and discussion.